A key brain difference between voice-hearing patients and voice-hearing healthy controls challenges the “continuum model”

There is a growing recognition that hearing voices is not always pathological.

24 June 2019

Share this page

Hearing voices that don't exist in the outside world is the most common form of hallucination experienced by people with a diagnosis of schizophrenia or related conditions and it can be very distressing. However, there is a growing recognition that hearing voices is not always pathological. Many mentally well people hear voices (or "auditory verbal hallucinations") – in fact, around 6-7 per cent of adults in the general population report having had such experiences at some point in their lives.

This has led some experts to propose a "continuum model" in which the same fundamental underlying mechanism leads to hearing voices in healthy people and in patients with a clinical diagnosis, but that for various reasons, such as a traumatic past, the experience is more troublesome and distressing for the patients. However, a new open-access paper in Schizophrenia Bulletin challenges the continuum model, finding an important brain difference between patients who hear voices and voice-hearing healthy controls.

The research team, led by Jane Garrison and Iris Sommer, recruited three groups matched for age, education, sex, handedness and overall brain volume: 50 patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia (or related conditions such as nonspecific psychosis or schizoaffective disorder) who hear voices; 50 non-clinical healthy volunteers who hear voices (at least once per week); and 50 healthy controls who do not hear voices.

The researchers scanned all their participants' brains, specifically looking at the length of a brain structure involved in "reality monitoring" or telling the difference between internally and externally generated experiences. For instance, a typical test of reality monitoring involves asking a person to read or imagine different words, and then asking them to recall which words they'd read and which they'd imagined.

Garrison and her colleagues wanted to test the idea that a problem with reality monitoring contributes to the voice-hearing experience in patients with schizophrenia, but not in healthy people who hear voices. To test this account, they used the scans to measure the length of a brain structure called the paracingulate sulcus (PCS) – this is the most frontal area of the medial prefrontal cortex and previous research has suggested that it is involved in reality monitoring. For instance, people for whom the PCS is completely absent (up to a quarter of the general population by some estimates) tend to struggle with reality monitoring tasks.

As they predicted, the researchers found that their patient volunteers had a shorter PCS than the healthy non-voice-hearing controls, and a shorter PCS than the voice-hearing healthy controls. In contrast, there was no (statistically significant) difference in the length of the PCS between the voice-hearing healthy controls and the controls who did not have hallucinations.

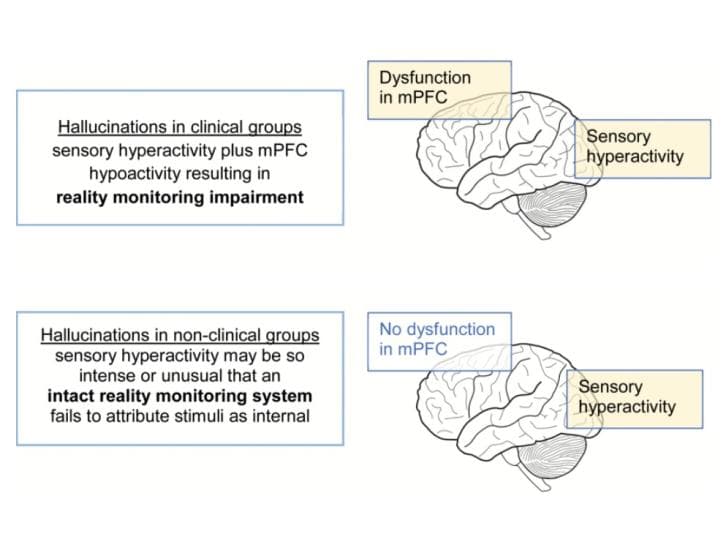

Garrison's team believe this result is consistent with there being two routes to auditory hallucinations (see image, above). For healthy people who hear voices, the researchers believe the origin is in hyper-activation of sensory parts of the brain involved in processing auditory information. For patients with schizophrenia, by contrast, they believe there is a sensory component combined with a problem with reality monitoring.

"These findings, together with our previous work, corroborate a model in which part of the mechanism underlying hallucinations is shared between clinical and nonclinical individuals with hallucinations," the researchers said, "while a second mechanism, compromising [in]adequate reality monitoring, is present in patients only."

This two-route model could explain some of the differences in the voice-hearing experience reported by patients and healthy voice-hearers, such as the lower frequency and shorter duration of the experience in the latter group. In healthy voice-hearers, hyper-activation of sensory areas is likely to be a relatively exceptional event, and their intact reality monitoring can also suppress the experience. For patients, by contrast, hyper-activation of sensory areas may not need to be so intense, and they may not have the necessary reality monitoring capabilities to inhibit or make sense of their hallucinations – consequently their voice hearing is more frequent and long-lasting.

The new findings also chime with past research that has suggested important differences between clinical and non-clinical voice hearers at a neurobiological level. For instance, patients with schizophrenia have been shown to have heightened synthesis of the brain chemical dopamine, potentially contributing to seeing intense meaning in sensations and experiences (known as "aberrant salience"), whereas non-clinical voice hearers do not show this same abundance of dopamine.

However, it's important to note that the new findings – and the two-route model – cannot account for some of the differences in the experiences of patients who hear voices and healthy people who hear voices, such as the more negative (angry, upsetting and controlling) content in the hallucinations reported by patients.

Also, it's worth noting that, among the healthy voice-hearers in this study, the length of the PCS was intermediary between the patients and non-voice-hearing controls. It's possible, the researchers admitted, that the reason the difference in PCS length between the two healthy groups was found to be statistically non-significant may have been due to a lack of statistical power. They said that replication of this study with larger samples could clarify this issue, adding that "…further research is [also] needed to to assess the extent to which the present results generalise to other nonclinical populations with hallucinations who may have different etiology and phenomenology of hallucinatory experience."

Further reading

—Paracingulate Sulcus Morphology and Hallucinations in Clinical and Nonclinical Groups

About the author

Christian Jarrett (@Psych_Writer) is Editor of BPS Research Digest