‘No, I don’t want to be sent on a yoga retreat!’

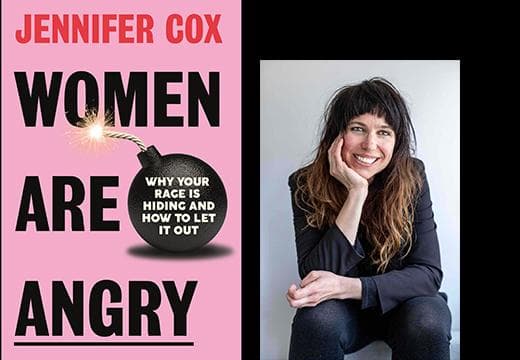

Jennifer Cox, psychotherapist and author of Women Are Angry, explains to Jennifer Gledhill why women are conditioned not to speak out about injustice, how stifled anger damages female bodies, and how to let it out…

04 July 2024

Share this page

You have worked extensively in psychology roles in psychiatric and forensic settings. What inspired you to focus your book on women's anger?

In my London clinic, I work with women from all walks of life, but the one constant in their lives is the sexist social structures and family expectations that are handed down to them through the generations. As women, we are taught to accept that things are a certain way or to kid ourselves that things have changed for the better. When we discover the injustices are still there, we swallow down the anger we feel, or send ourselves to a retreat believing there's something wrong with us. It's collaborative gaslighting on a massive scale.

After the murder of Sarah Everard in 2021, by police officer Wayne Couzens, I just thought, 'I can't keep these feelings to myself anymore'. I opened my laptop, started to write, and my thoughts just flowed and flowed. Another chapter came soon after I heard the news about Roe v Wade [in 2022 the US Supreme Court ended the nationwide right to abortion]. Really though, my female clients wrote this book for me. I was writing about all the situations they told me about where they have swallowed down their anger.

What are we most angry about?

Sexism and gender inequality. It still exists but women are conditioned not to feel the most obvious signal for this injustice: anger. When frustration or irritated confusions surface at an incident, we don't accept that emotion at face value… instead, we subdue it and shrug it off. Our bodies then are left to make sense of what's happening:

As I say in the book, 'our anger comes from the gaslighting we've grown up with, the pretence that we're living in a world which has changed for the better.'

And how does that anger show itself in our bodies?

Our anger doesn't present very often in its straightforward form. It's disguised psychologically as panic attacks or OCD, and very often physiologically through chronic pain or migraine or fatigue. It is displaced anger. Other emotions come in such as sadness, tearfulness, shame, numbness and guilt. They push the original rage out of the way and sit more easily in our minds and within the role that society has carved out for us.

But psychotherapists are often focused on what is underneath a client's anger, treating it as a symptom of something else rather than purely rage…

I agree. It's like anger is a problem, and it needs diffusing. The wellbeing model has always been about 'calming things down, letting it go. Breathing it all out!' When I've tried to do that with anger, it doesn't respond. Nothing happens. It just migrates a bit. I've pushed it somewhere else, but I haven't got rid of it. We're constantly being told to accept our anger as stress, to self-soothe, go to a spa, but no, I don't want to go to a yoga retreat. This kind of solution is often put on women, isn't it?

Was there a lightbulb moment when you thought, 'hang on a minute, I'm doing everything I can to diffuse how I'm feeling, maybe I am just truly angry!'?

Absolutely. I know what anger in a room looks like – my training and background was in forensic working with men, violent men. I had learned to sit with it and how to handle myself around it, but I just did not expect to see it in private practice with so many women. I found myself feeling similar, kind of counter transferential feelings. That's when I thought why am I feeling the same here as I was in the prisons? It doesn't make sense. And then suddenly I started realising, no, it really does make sense. You know, we've all got these animal drives in us and just because we look the way we do and have the bodies we do it doesn't mean we don't often have similar impulses.

The chapters in the book follow a woman's life cycle; 'from cradle to grave'. It was quite scary to read how girls are treated differently from day one, either consciously or unconsciously.

From the earliest point in our lives, we're subtly coerced and co-opted into various roles. We're instructed in feminised symbolism from the second we're born; softness, cuteness, homeliness, pastel insipidity, infantilism, tweeness, care; every pink pyjama or glittery sandal or eraser says it. We need to start thinking about how girls' minds begin to develop differently according to this influence and how they are reinforced by family and society expectations. But I am conscious of saying in the book that all is not lost. Things can be different, and we must foster that hope. I think any change starts with proper conversations and being able to identify our own feelings and talk about them as clearly as we can.

You talk about 'the workaround' stage that affects adult women. Can you say more about this?

I describe the 'workaround' as when women seem to magically distort time in order to render themselves visible or invisible depending on what others need. They do it to be present in all the places they're expected to be, for those around her; children, men and other family members. This was especially highlighted during Covid when women took on even more responsibility of care on behalf of the wider family. Is it any surprise that women are exhausted or 'depressed' or 'anxious'?

Was there a fear when writing the book that women would recognise their own experiences of power abuse but feel powerless to do anything about it? Was it a worry that they will just feel even more rage?

I felt so worried about that. Anger is a very emotive topic. Talking about this stuff, sometimes feels like I'm opening a cage of wounded animals and I'm going to get scratched in the process. For example, on Instagram yesterday, I said something like, 'What's making me mad today is the volume of women I hear having to psychologically mother men who are too frightened to take responsibility for their own feelings. These fears come across as anger and then women are frightened of the men, and placate them, and try to please them, so that everyone's soothed, and they're not going to be hurt. Women, please, we've got to stop doing this'. Anyway, lots of people commented and one woman said, 'but how do we stop doing this? It's all very well saying it, but how do we stop?'

Exactly, how do we?

In the book, I've really tried to reaffirm that I'm a woman trying to live in the world and I acknowledge how hard it is and also struggle myself. I don't have all the answers. However, the book is full of case studies, of real-life situations that women I've worked with have found helpful. At the end of each of 'life-cycle' chapter, I summarise what we can do for other women and ourselves. The third part of the book is how we can all make changes that use anger 'better'; this includes recognising how it feels in our bodies, verbalising what we need and bringing men and boys into the conversation.

I loved that a suggestion in the book is for women to start saying the word 'Vagina' 16 times a day…

Even in the UK, women's health is under-researched and under resourced. Men are still making the decisions about our reproductive rights and our bodies. Talking openly about our bodies is such a simple change we can all make to challenge body shame. Imagine looking your male co-worker/boss in the eye and saying one of your 16 'vaginas' to him. That locus of shame and vulnerability can finally become a source of audacious mental power. Do this with other women in your families or at work too so it becomes easier to be open and honest about our bodies.

What could men be doing to help change the narrative?

I'd like to see men being taught how to take on more accountability, and this starts at home and in primary school. We need to teach kids how to have conversations in ways that are respectful and give them the opportunity to talk about their feelings in more eloquent ways. Let's even look at what is happening in playgrounds, and at birthday parties where it's boys on one side and girls on the other. I would love to see more men being taught to stop blaming women for the clothes they're wearing, or not being clear enough around consent. We need to be teaching them these skills from the get-go. But employers need to get with the programme too. Why aren't more offering shared paternity leave? Or when there are programmes trying to get women to be more assertive and ask for pay rises, what about training programmes for men where they're taught how to allow women space and respect?

And should women be playing more of a role in respecting and supporting each other?

Absolutely. I explain as to why it's almost an evolutionary footing for us to put other women down. It can be tempting, and we really need to fight the urge to do so because we shoot ourselves in the foot every time we do it. And I didn't even really touch on what we do to women in the media, or women with any kind of power, because that just feels like a whole other book.

I'm not sitting here saying that I have all the answers and get everything right, but as a therapist, I know about the relational richness that women can bring each other, how it can be so healing and a real antidote to anger.

Are you hopeful that we can make changes?

Yes, I am. In the third part of the book, I explain how we can learn to regulate our bodies, how we can express more clearly about how we are feeling in the moment and what we need. I suggest we talk about everything in families, schools and workplaces with no topic barred, from periods to domestic violence. With a more straightforward attitude to our physicality and discussion of our embodied experience, we can more easily ask for the things we need in life – from our families, partners and healthcare providers to employers and eventually politicians. I really want to encourage people and plant the idea that this is all possible. Let's try it. There's really nothing to lose.

- Jennifer Cox is a member of the British Psychological Society, the British Association for Counselling and Psychotherapy and the London Neuropsychoanalysis Association. Women are Angry: Why Your Rage is Hiding and How to Let it Out by (Bonnier Books) is out 4th July.